|

Searching the Internet For Historical Information by Stevieo first published at searchlores in July 2004 Part of the searching essays & of the evaluating results sections. |

|

|

Searching the Internet For Historical Information by Stevieo first published at searchlores in July 2004 Part of the searching essays & of the evaluating results sections. |

|

Searching the Internet For Historical Information

Historical information can be hard to find on the internet.

This paper starts by listing a few of these difficulties.

The rest is a live experiment where I try to figure out

how to do historical research using the internet.

I hope to provide some tips to help others do research

on the internet.

History is Hard Work

Asking questions about history can be a lot of work.

Here's how Sir James George Frazer opened his preface to

the abridged edition of

The Golden Bough.

The primary aim of this book is to explain the remarkable rule

which regulated the succession to the priesthood of Diana at Aricia.

When I first set myself to solve the problem more than thirty years ago,

I thought that the solution could be propounded very briefly,

but I soon found that to render it probable or even intelligible

it was necessary to discuss certain more general questions,

some of which had hardly been broached before.

In successive editions, the enquiry has branched out in more and

more directions, until the two volumes of the original work

have expanded into twelve.

The task of gathering and evaluating information

can be a lifelong project,

even for a seemingly simple question.

Here are just a few of the difficulties.

For primary written material

For non written material

Secondary sources add more difficulties

Researching on the internet adds some difficulties, but also solves a few problems.

Finally, there are some general rules about information that apply, particularly for the internet.

A Simple Beginning

The naive approach to searching is to put some relevant words

or phrases into a search engine and look through the first few

results for a quick answer. This is sometimes successful.

It is a valid approach when you need a simple overview,

need to verify a simple fact, or when you know where

something is but don't know the URL.

It is also successful when the search engine is tuned to provide

the kind of answer you're looking for. For example,

the rage today is to rank web sites by popularity.

If you're looking for one of the most popular sites

for a given subject, this naive approach is likely

to be successful.

For this experiment, I chose a random sentence from a random book on history.

The book is the 1964 Norton Library Press edition of the 1952 second edition of

A History of Greek Religion by Martin P. Nilsson,

translated at some point from Swedish to English by F. J. Fielden.

I opened to a random page (p 187), and near the top found the following sentence:

The prohibition against pouring libations

with unwashed hands is as old as Homer.

Using the naive approach, I pick out the important words

and type the following query into google's query window.

"unwashed hands" libations homer

In response, google returns exactly one link to a pdf file entitled

Homer: The Simile as Textual Stratagem.

I open the document in acroread,

hit Ctrl-F, type in unwashed, and find that the pdf contains

the word "unwashed" exactly once.

It is the Greek original with English translation of

The Iliad book 6, lines 226-8.

I fear to pour out the gleaming wine to Zeus

with unwashed hands; nor is it permissible to pray to the son of Kronos

who is shrouded in the clouds when spattered with blood and gore.

Was this search successful?

It may seem so, but it fails on a number of counts.

The most important problem is that

I never defined what I wanted to find, so

there's no way to determine whether or not this

answers the question.

What Were We Searching For?

Let's take another look at that quote.

This time I'll pretend I'm reading it for the first time

and that something about it caught my interest.

The prohibition against pouring libations

with unwashed hands is as old as Homer.

Now, that's a bold statement,

even for someone as respected as Mr. Nilsson.

There's no footnote for this sentence.

The context is purification rites and taboos,

but that tells me all of nothing.

For all I know, Mr. Nilsson made this up.

Now this is something specific I want to find out.

Is it true that this prohibition is as old as Homer?

We already did the search.

We'll evaluate those same results to see if this was a

successful search to the new question.

I fear to pour out the gleaming wine to Zeus

with unwashed hands; nor is it permissible to pray to the son of Kronos

who is shrouded in the clouds when spattered with blood and gore.

Do the results answer the question?

That depends on what you already know.

This may seem to answer the question,

but it's not entirely clear whether or not this prohibition

applies only to hands drenched in blood.

It's also not clear whether it applies to pouring libations

or only to praying.

It also only talks about Zeus, not the "deathless gods",

or the gods and daemons in general, or heroes.

If you look at several

translations, or if you merely read that pdf document,

you also know that there's a translation question here.

What we did learn is that in this particular case

someone adamantly refused to pour libations to Zeus while

his hands were drenched in blood.

If you read the book, you know that this is Hector,

and that he had just returned from battle,

and his hands were drenched in human blood.

So this doesn't prove that there was a general prohibition

against pouring libations with unwashed hands.

All it proves is that Hector adamantly refused to pour

libations to Zeus while his hands were drenched in human blood.

If you merely read Homer, you'll have a hard time

proving that there is such a prohibition without

understanding a few things about Ancient Greece.

This is my second rule for primary sources.

You almost always need considerable background knowledge

to evaluate primary sources.

Certainly you cannot evaluate them efficiently without

such knowledge.

Probably the first thing to know is that Homer is consistent

in his formulaic repetition of certain themes. This is so well

known, it has a name: the Homeric Epithet. For example, whenever

a warrior falls in battle, we hear the clanging of armor as he

crashes to the ground. The washing is also formulaic, especially

in The Odyssey where we read over and over

"A maid servant then brought me water in a beautiful golden

ewer and poured it into a silver basin for me to wash my hands, and

she drew a clean table beside me".

The servant, silver basin, washing, and drawing of a clean table

all occur over and over again in nearly the exact same words.

If you read The Iliad carefully you might

notice that people only wash their hands before praying to or pouring

libations to a deathless god, which essentially means the Olympians.

You do not read about any required washing of hands

before pouring libations to the dead, or to minor gods,

which they also did.

Finally, you can read about Achilles pouring to

Zephyr and Boreas (the west and north winds)

and also pouring to his fallen friend Patroclus,

while building Patroclus' funeral pyre,

all the while refusing to wash off the blood of battle,

Patroclus' blood, or the blood of the pyre sacrifices.

He also refrains from the feast, thus getting

out of the need to wash for the pouring to the deathless gods.

If you want an explicit statement of the prohibition,

you can find it in Hesiod

[Works and Days II 724-6].

But Hesiod lived after Homer, so this too proves nothing.

But at this point, we have enough information to make

a convincing argument.

In every case in The Iliad,

people wash their hands

before pouring libations to the deathless gods.

It is unlikely that Homer made this up and then went

through the trouble of dragging out the servants with

their water and napkins along with the wine

every time the meal ended.

(In one case the washing is not explicitly mentioned,

but it is implied because the servants would not forget.)

Hector's adamant stance makes it almost certain

that Homer knew of a prohibition in some form.

We can judge its precise form from the actions of

Homer's characters. They washed their hands before pouring

libations to a deathless god, but did not (necessarily) wash before

pouring to the dead or to the minor gods and daemons.

The explicit statement by Hesiod verifies that precisely

such a prohibition did exist, if after Homer's time.

This is precisely the form the prohibition took centuries later

(barring some minor variations).

Ritual is one of the most conservative of human activities.

It is unthinkable that Homer could describe a prohibition

so precisely and take such care to point it out in every case

if the prohibition did not already exist in his day.

The Odyssey is an even more striking example

of the consistent, formulaic repetition of this ritual.

Evaluating the Results

Using the simplest approach to searching

got me a single search result that contained

enough information for me to solve most of the problem.

I also needed to scan the actual primary source,

The Iliad, albeit in translation,

and look up the book and line numbers

in Hesiod's Works and Days

where I knew beforehand the prohibition could be found.

I knew enough of the subject to do the rest.

You may have needed to do more work.

If you're not familiar with Ancient Greece, you

need to first learn that Hesiod explicitly mentions the

prohibition, or at least that this prohibition existed later.

This could take some time, but is not a difficult problem.

You might also have missed the extra point about not

washing before pouring libations to the dead, a point

that helps strengthen the argument.

This is also extra work, but you'd have to be pretty sharp

to catch it. In any case, it's not strictly necessary.

If you're not familiar with history at all, you probably

couldn't construct a proof.

You might even be unconvinced of this proof or any other

that falls short of irrefutable logic, causing you to

expend untold extra work looking for unnecessary

and difficult material, and probably failing in the end.

This is exactly how a search should work.

Go back to the first two rules about primary sources.

If you don't have the background, then you need to do some work to acquire it.

I'd add that you tend to search for things that are near your level

of knowledge and your subjects of interest.

It's highly unlikely that anyone would search for information about

a 2800 year old prohibition without some previous exposure to the subject.

If you did find the need, you might be better off finding someone to help.

But we need to answer the bottom line question.

Was this search successful?

No doubt it solved the problem for me.

So for me, this was a successful search.

For someone without the proper background,

it is a miserable failure in more ways than I can count.

Improving the Naive Approach

Someone suggested we change the query.

Of course we have to do this.

Let's try the obvious mechanical changes first.

A query like "unwashed hands" libations homer is just one facet of the quarry.

The quarry is more or less like a diamond, we need to turn it around :)

The examples below are from google too.

libations homer "washed hands": gives nada.

libations homer "washed * hands": gives 37, and they look promising.

libations homer "handwashing": 7

(don't forget the variants: hand-washing, "hand washing")

libations homer "wash hands": 1

libations homer "wash * hands": 29 (!)

then the same variations with "libation" in the singular.

Of course, you can achieve the same effect by designing a boolean string...

Rephrasing in any conceivable way, using synonyms,

changing the sequence of words, changing expressions, even changing the spelling,

that's what I'd use if the first cast of the net brings too little.

First things first.

These techniques are essential.

While translations of classics tend to use certain phrases,

there's usually more than one set of phrases,

and they vary by language.

For example, you should try: wash, washed, washing, unwashed,

unwashen, unclean, and maybe others.

Notice the ancient language, especially unwashen.

This is something peculiar to classics.

But each area has its own peculiar language.

You should find out and use the phrases that your targets use.

I tried all of these suggestions on several search engines.

and got as many as 600 results.

One thing to note is that trying the same query a second time

might give different result. This is normal.

The results you get vary depending on the

time of day, day of the month, how busy the servers are, etc.

In all these results, there were only a handful of any relevance.

If you're not familiar with the subject, you might not even spot them.

It's pretty clear that more isn't necessarily better.

Randomly playing with word order, word tense, and synonyms

is important, but it only gets us so far.

We need a better way.

Abandoning the Naive Approach

The best way to improve our chances of finding something is to

have the background knowledge needed to find it.

We need even more knowledge to evaluate what we do find.

Without this knowledge we might not recognize that

something we run across is significant.

The original document we found was relevant mostly because it

pointed to The Iliad.

(In fact, there's an interesting discussion about the translation

that is quite relevant.)

We would have been better off just finding that in the first place.

Even if we found it, it isn't enough to answer the question.

We need some background information to find the whole answer.

Understand the Information

The first thing to do is understand what we're looking for.

Let's go back to the original statement

and consider what we need to know about it.

The prohibition against pouring libations with unwashed hands is as old as Homer.

First, you should read an overview of what The Iliad is about.

We already know it's important, since it came up in our original search.

Then we need some background information.

What are libations?

If you don't know, look it up.

Since it looks like a thing that you can pour, you can even use a dictionary.

Again, we use a very simple query for "libations" or maybe "libation".

The dictionary says:

The original quote talks about pouring libations,

so we can guess that the first definition is the right one.

Who is Homer?

Let's get some background information on him.

A simple search engine query for "homer" should get us what we need.

For now, don't try to find anything connecting him to prohibitions or libations.

At this stage, we only want some general background on him.

This background will help us ask more intelligent questions later

when we try again to find the connection.

Homer was a poet in Ancient Greece.

He's important because his version of the epic poetry was written down,

probably around 850 BCE.

The most important of his poems are the epic poems

The Iliad and The Odyssey.

We're already familiar with one of those.

So now we have the who (Homer), what (Iliad, Odyssey),

where (Greece), and when (850 BCE).

What about the why?

For the why, we should probably ask if there's some significance

to "as old as Homer".

We might find out that Homer's work is the oldest Greek writing.

This is significant because it makes it very difficult to find

out if this prohibition existed before Homer.

If we dig deeper, we might find out more.

Homer's poems, along with Hesiod's work, form the basis of Greek religious thought.

This is definitely significant, since what we're looking for

is almost certainly a religious prohibition.

At this point, you might want to get some background on Hesiod.

The main things to learn are what he wrote, and that

he lived about 100 years after Homer.

Whatever you find out, you'll still need Homer's work for the proof.

Once you learn this, you should repeat the original search using

hesiod instead of homer.

You should realize that your ultimate target is a primary source,

a translation of Hesiod's writing, even if you need to read a few

secondary sources along the way.

(Remember to use the word variants, and more than one search engine, if necessary.)

If you follow this path, you'll find the explicit mention of the prohibition in his

Works and Days.

A Biased Detour

Unfortunately, some people claim that Hesiod came before Homer.

On a simplistic level, you should never just believe the first

or any source you read.

The real problem is knowing when you've done enough.

Just how much effort do you really want to expend?

And how sure do you need to be?

Unfortunately, more isn't necessarily better.

You might still not have a good answer even after reading everything

ever written on a subject.

I'll refrain from getting philosophical here.

Instead, it's probably a good idea to inject your own bias into the process.

As the rest of this section points out, everything you read will

be biased, so you may as well filter it through your own biases.

Having more than one answer is actually a pretty complex problem

because it operates on many different levels.

It goes well beyond a mere

dispute of the facts, or what we normally think of as bias.

Some schools of thought believe that bias is an inherent

part of what historians do.

They go so far as to say that history is the study of historians.

I'll be blunt and make no excuses.

In this case historical facts are irrelevant.

There is a tradition that Homer comes first.

On one level, "history is the study of historians" means

accepting that Homer came first because most historians say so.

Digging further means discovering how and why they reached those conclusions.

In any case, Homer's work represents the bardic tradition--the

early Greek mythos--which definitely preceeds both Homer and Hesiod.

Call it a simplification if you like.

Strict adherence to facts is only one method among many.

There are different schools of thought among historians, and all but one

or two of them reject the strict adherence to facts.

This doesn't mean they dismiss facts, but rather they simplify and add theories.

A good historian would point out the dispute, but might only do so by slipping

a word or two into a sentence like "probably", or "by most accounts".

Why bother with facts when what you really want is to understand?

The dates of when these guys lived are raw facts.

You can use them as is, and do nothing with them, except put them in a chronology.

Or you can make use of the dates for very limited, specialized research.

Even if it were proved that Hesiod came first,

it would be deceptive to let that get in the way of a clear understanding

that the lyric poetry in Homer predates both Homer and Hesiod.

I asked before how much effort you want to put into the search.

The answer, of course, depends on what you want to get out of it.

If you're looking for some coherent background, you might be better served

getting one biased version from a reliable source, kind of like the advice

you get when you ask someone you trust.

(See "Sielaff's lessons" on the "Evaluating results" page on searchlores.)

Of course, that assumes the bias is appropriate.

A particular point of view that's perfect for one use

might be useless for another purpose.

For example, there's a French school of the history of Greek religion

(Zaidman and Pantel) that places everything within the context of the

city-state. It's a very useful point of view to learn about the later

developments when the large temples were erected.

Unfortunately, it biases the entire discussion by placing the center

of Greek life in the city, while its heart was always in the countryside.

(Some historians even claim there never was a proper city in Greece.

Greek life was about small communites, not great cities.)

Also, by deemphasizing the earlier history (pre 5th C),

the continuity as well as the early basis for the later crisis

are completely missed.

Contrast this with Nilsson whose focus on the countryside

shows the continuty clearly--to the point that you can understand

some things that are still with us--yet this emphasis makes it

very hard to understand how any Greek could have accepted a

nationalistic religion that brought about the empire and the

grand temples, probably setting the pattern that Rome would

later bring to new heights.

Likewise, a proper (non-religious) history might cite the

Persian wars as the cause for the empire, and it will probably

explain the crisis clearly, and it will also be able to show

continuity in some things from the latter part of the 5th century

through today (Philosophy, Science, and maybe Democracy),

but such an emphasis can too easily overshadow the more

subtle continuity in folk religion and social life that

dates back to at least the 9th century, if not the 15th--the

continuity that Nilsson illustrates.

(Greek religion is unusual in that it's not distinguished from civil

life in general, unlike nearly every other great civilization.

This makes it difficult to separate religion from any historical account.)

These are all examples of bias.

I hope the time I spent on them illustrates how different

starting points can lead to different conclusions.

Also, the level at which you want your information is something

you need to consider as part of the preparation for any phase of

a complex search, like this learning process approach to history searches.

Do you really want to read linguistic analysis of ancient Greek, and

arcane discussions about phrases and word comparisons?

I sure don't.

If a particular point interests you, then learn more about it.

If the goal is just to get background on something to improve the later

stages of the search, then even wrong answers can be useful.

Does it really matter if you get incorrect directions that get you

where you want to go?

If it does matter, or if you're curious,

then you just need to do more work. Or maybe it's play.

Stop & Think

We're trying to find out if a prohibition existed in Homer's time.

If we can prove that Homer knew about it, we're done.

We're also done if we can prove that someone before Homer knew about it.

Since noone in Greece wrote before him, that might be hard to prove.

Or is it?

Homer's epic poems are about the Trojan War. The heroes in it are people

who lived in the area before it became known as Greece.

With a little digging you should find out that there were two main

cultures in the area, the Mycenaeans, and the Minoans.

Since the Minoans are centered on the island of Crete,

we should probably start with the Mycenaeans, who lived on the

mainland of Greece.

Did the Mycenaeans have writing?

A quick search on "mycenaean writing" should yield results.

Linear-B was a syllabary (a set of written symbols that represent syllables)

used in Mycenae during the 14th and 13th centuries BCE.

The language used was an early form of Greek.

Linear-B is derived from Linear-A, used for writing by the Minoans,

who had an entirely different language.

Looking at the dates, we find that Linear-B is used in the 13th century,

and writing doesn't occur again until the 8th or 9th century with Homer.

This is why those years are called the dark age.

This isn't very hopeful.

If we can find the prohibition in Mycenaean times,

we'd still have to show that it existed after Homer

(the proof of which is in Hesiod, or in many books after Hesiod's time)

and also that the practice was continuous.

This wouldn't be easy.

We already talked about how difficult it is to prove

this kind of negative using artifacts.

We should probably concentrate on using Homer to prove it.

Grab a copy of The Iliad and search through it

for libation or whatever word the translator uses.

We have an advantage here in that the language within

a single translation is almost certain to be consistent.

A little gift we get in the case of Homer's poetry.

He likes to reuse phrases, and any translator worth

their salt will stick to this tradition.

Unfortunately, this yields nothing.

Search The Odyssey and you get the same result.

There is no explicit mention of any prohibition in Homer.

We should probably find out whether this prohibition existed at all.

If we were lucky, we already found out about Hesiod,

in which case we know the answer.

There are some other things we might try to learn,

some will prove useful, some won't.

For example, if the prohibition did exist, we might try to

find out when it started. (But we won't do this yet.)

In any case, we need to find out about the prohibition.

Back to the search engines.

More Bad Search Results

We already know we're dealing with Greece, so let's search for

"libation AND greece AND prohibition".

A few queries to try are:

Not very successful. In fact, it's getting worse.

We've just bumped into three rules of internet searches:

Search engines are dumb.

The caveat about bias in secondary sources applies

especially on the internet where misrepresentation and

deceit are the rule, not the exception.

You'll probably notice by now that there's a lot of stuff on the

internet related to modern pagan cults.

These are modern people who practice the ancient Greek religions.

The subject is very close to the one we're interested in.

Almost all of the words we use in any query are going to bring

results from this group.

For now, if you realize it's a modern cult, run away.

This has nothing to do with being a cult,

it's just that, for the most part, they are a very bad

source of information on the real ancient Greek religions.

Another large problem area are Christian sources that try

to either discredit Greek religions, or highlight them

in a positive way. The purpose of both of these is to

bolster the validity of modern ideas.

Either way, most, but certainly not all of these sources

give a distorted point of view when your purpose is to

learn about the actual Greek religions.

History isn't exactly a popular subject, but some of the

issues you deal with are. Sometimes, a more popular treatment

can hide the stuff you're interested in. If this happens with your subject

it can be hard to get past the more popular stuff to

the things that interest you.

Anything to do with Ancient Greek religion

is hidden behind the more popular subjects of modern cults

and Christian apologists.

It would be nice to have a better way to get past the

stuff we don't want.

Going Further

There's no real point in discussing more about choosing different

words for search engines because the arrows that hit the targets,

and the results you get vary so much depending on what you're looking for.

If you need ideas, there's a lot of good stuff on searchlores.

I only went through a few of the simpler techniques to

highlight some of the problems that are specific to history.

The real issues are all about evaluating the material

and asking the right questions to find the next piece of the puzzle.

If you're interested in taking the research further,

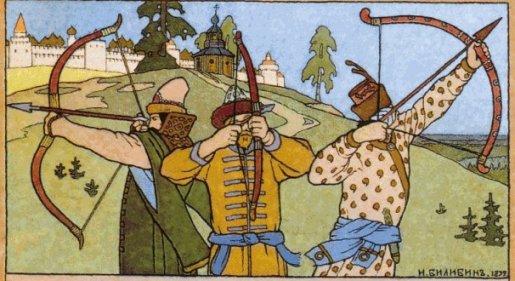

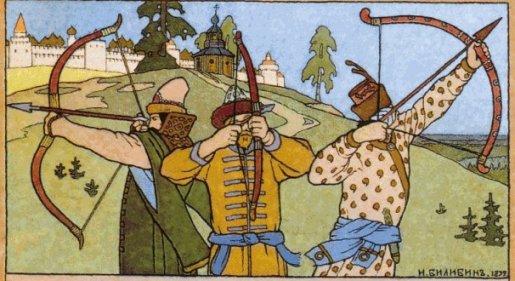

try a picture search to learn what you can from before Homer's time.

Another approach is to compare the practice of different cultures.

If you're brave, you might even look further for the prohibition,

but I'm not that brave.

Or, you could just keep plugging at the written material from

later Greece to follow how the practice changed.

Just don't get too sidetracked.

Also, you might want to look back at the list of difficulties

and see what you disagree with, and what solutions you have.

In the end, I find the internet very useful to get

an overview of related issues, or to get background on something,

or even to find out which sources to use off the internet.

I'm constantly looking things up while reading books, especially

on a new subject.

Some useful general tools you might want to bookmark are picture

dictionaries and a thesaurus for terms in archaeology, art,

architecture, geography, geology,

and then some maps and general timelines for the areas and time

periods you're studying and those nearby.

But I believe you still need a good library to do serious research.

The internet just isn't up to serious historical research yet,

except for a few, mostly recent topics.

The situation is constantly improving for primary sources,

but I think the lack of good secondary sources is going

to remain a problem for quite a while. I hope I'm wrong.

Unfortunately, at this point I have more questions than answers.

Someone said "I may not get my answer - but learn a lot of History".

If the article helped get the critical thinking process going,

it did its job.